In its current form, Pittsburgh’s airport boasts more oddities than luxuries.

A Tyrannosaurus rex from the natural history museum towers over travelers. Piped-in classical music by the local symphony orchestra plays overhead — at every turn and terminal. Standing guard together by the escalators are statues of Pittsburgh Steelers player Franco Harris and a young George Washington wearing an incredibly lifelike wig.

The quiet airport looks more like a rust belt mall designed in the ‘70s than a transportation hub, and it’s hard to imagine Silicon Valley figureheads wheeling their Away suitcases past these sights (and the gift shop selling novelty nightgowns) as they head for town.

Both the city and its airport, however, are in the midst of major redevelopment.

In another chapter of its commercial boom, Pittsburgh has hired two firms to design a new terminal as part of a $1.1 billion overhaul. The decision may have been influenced by the fact that Amazon is considering building its HQ2 at a 195-acre site nearby. Or, it’s simply the need for a more elevated transportation hub in line with the changing city, where commercial rents are rising as players like Google, Apple and Uber make homes out of old mills and warehouses.

With Amazon shopping neighborhoods and activists trying to defend theirs, the Pittsburgh of tomorrow can seem like a tale of two cities. Can the former town of steel become a beacon of tech? And what happens to the city’s commercial landscape as it welcomes a next generation of movers, shakers, and Yinzers?

In recent years, the city has attracted new corporations due to its affordable real estate, low cost of living and steady stream of engineering talent graduating from the top research universities. Some have predicted Pittsburgh will become Appalachia’s own Silicon Valley, and local government officials been quick to accommodate tech beacons eyeing development in the city.

“You can either put up red tape or roll out the red carpet,” Mayor Bill Peduto said of Uber in 2016. “If you want to be a 21st-century laboratory for technology, you put out the carpet.”

This attitude has helped Pittsburgh make it to round two of Amazon’s search for its next HQ. But the locations that Amazon is considering in the city include spots already well on their way to becoming tech hubs — sans assistance from Jeff Bezos.

There’s the Strip District — a warehouse and grocer neighborhood that has been transformed in part as “Robotics Row.” Apple and artificial intelligence company Argo AI are already at home in the Strip, and a 105,000-square-foot office and research and development building is currently being built alongside a former wholesale produce terminal.

Previously slated for demolition, the five-block-long market will be converted to retail shops, offices and restaurants meeting LEED Silver standards, which could attract additional corporations to the neighborhood.

Some have compared the area to Seattle’s Pike Place Fish Market back in Amazon’s hometown, and the Strip District is where new and old Pittsburgh meet. International grocers and bakeries serve up regional staples, included the beloved pierogi, beside tee-shirt stands that will outfit you in a full wardrobe of black-in-gold for less than twenty dollars. You can walk into any coffee shop and meet generations of Yinzers who’ve worked in the mills and the market, including some who resist the idea that the steel town was a ghost town before tech moved in.

City Councilwoman Deb Gross, whose district encompasses the Strip District, has opposed the use of a tax increment financing (TIF) to redevelop the produce market. An area must be declared blighted to qualify for a TIF, which means the project will not generate tax revenue.

The Strip hasn’t been blighted for many years, Gross said, and it’s important to address what this project is incentivizing. “Are we incentivizing what some people call a playground for the rich,” Gross asked. “I mean is that what you’re going to vote for today? Who is this development for?”

Gross has also brought up concerns from residents about the cost to recent commercial spaces in the redeveloped produce market. Will local sellers be able to afford it, or will the Art Deco and Modern-style market become a parade of national chains?

“That’s a very big building and they’re gonna ask for market rents,” local business owner Larry Lagattuta told PublicSource. “And the only people who can pay for market rents are people who are going to bring something into this neighborhood that have nothing to do with this neighborhood.”

The produce terminal is not the only commercial real estate project underway in the neighborhood though. Pittsburgh City Councilors have approved a permanent zoning plan for 35 miles along the riverfront bordering the Strip District. The first commercial building in this new landing will have 18-foot ceilings on its first floor and a direct loading dock to attract tech buyers.

“We’re in the Strip District and it’s the center of automated vehicles and artificial intelligence,” Shawn Fox, president of Bridgeville-based RDC Inc, told NEXT Pittsburgh. “For robotics users, that ceiling height and direct loading dock can create a R&D-style space on the first floor.”

Uber also has its Advanced Technology Group facility in the Strip District, and the company’s autonomous cars can be spotted whirling through the city’s many neighborhoods. Uber moved its Advanced Technologies Center and test track for autonomous cars to Hazelwood Green in 2016. The area is also in the running for the new Amazon headquarters.

The other possible HQ2 sites are 28-acre former Civic Arena site in the Hill, the previously mentioned 195-acre site by the airport, and an 168-acre location by an old steel furnace outside the city. If Amazon selects any of these five spots, Mayor Peduto said he expects the 50,000 jobs to be split 50-50 “at a minimum” between locals and transplants.

Greg LeRoy, the executive director of Good Jobs First, told local media outlet PublicSource that he estimated only 15 to 20 percent of the Amazon jobs would go to Pittsburghers. Aaron Terrazas, the economic research director for Zillow.com, gave a more optimistic prediction. In a housing study of HQ2 finalists, he predicted that local residents would secure 30 to 40 percent of the Amazon jobs.

These predictions would mean that anywhere between 25,000 to over 40,000 newcomers would set up shop in the steel city. An influx of new residents earning high salaries would drive up housing costs, which “means more low-income households will not be able to afford the housing,” said Nan Roman, the president and CEO of the National Alliance to End Homelessness.

This speculation is already pushing real estate values up though, as people begin to buy homes and properties with the hopes on flipping them for Amazon newcomers.

John Petrack, the executive vice president of the Realtors Association of Metropolitan Pittsburgh, pointed to the purchase of 18 properties near Hazelwood Green by a New York company. Terrazas has predicted that rent in Pittsburgh could rise 1.9 percent if it wins its HQ2 bid.

Demand for housing and commercial space has steadily climbed in recent years, as the city grows trendier. Pittsburgh’s food scene has exploded, as chefs enjoy lower risks and higher rewards there than pricier markets. Neighborhoods full of craft brew bars and vintage stores have caused Pittsburgh to be named the new Brooklyn (much to the displeasure of actual Pittsburghers), and local college grads often decide to stay put in the hipster-friendly Lawrenceville neighborhood. It’s hard to count the number of media outlets who’ve published surprised takes on the city’s charm, and all of the free PR isn’t for naught — or to no effect.

Office rents have risen at an average of $25.92 per square foot for top-tier buildings. In a package of stories on Pittsburgh, Geekwire reported that landlords are asking close to $40 per square foot in new buildings in neighborhoods near the universities where most of the tech activity is located. In comparison, new buildings near Amazon’s headquarters in Seattle go for $42 per square foot.

Home values rose 16.1 percent to $143,500 over the past year, with apartments near tech hands going for a 50 percent premium over the city average at more than $1,500 a month, according to RentCafe. An 18 percent rise in millennial population from 2010 to 2015 is also revitalizing the housing market but sometimes at the cost of current residents.

Pittsburgh has lost a quarter of its black population since 1980 due in part of disruption of primarily African American neighborhoods by large commercial real estate decisions. Activists from at-risk communities have often noted how they’ve often felt left out of conversations or development decisions in the city.

Google’s office in a converted Nabisco warehouse is part of Bakery Square, an urban strip mall of sorts with coffee shops and chain, such as Anthropologie and L.A. Fitness. For Carnegie Museum of Art’s blog Storyboard, Nick Coles notes how the developer of Bakery Square received major public funding because the project borders a blighted neighborhood, “whose mostly black residents have hardly benefited from the action.”

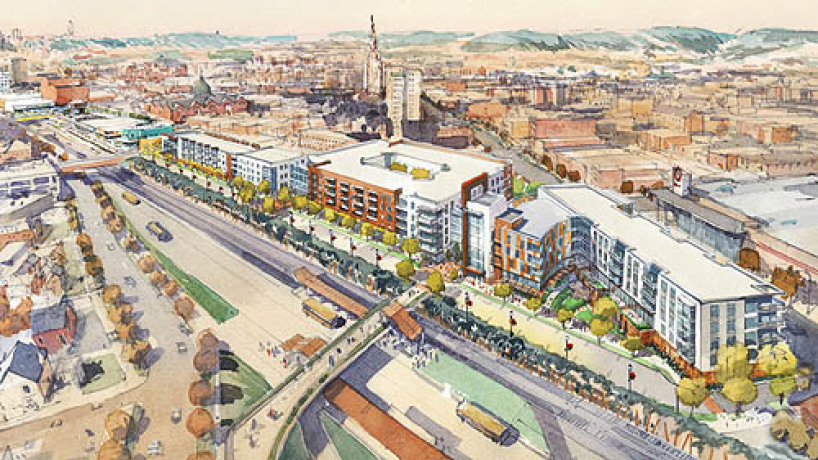

Coles, a local professor on working-class literature, further unpacks the inequality at play in Pittsburgh’s commercial develop by pointing to a Transit-Oriented Development project in East Liberty. This project includes a $77 million privately-funded development of multi-family housing units and 43,000 square feet of retail and commercial space, as well as a new bus station and other traffic infrastructure.

No units in the apartment project have been reserved for tenants whose income is below the city’s median income, while the project also received $3 million is state transportation grants. The Pittsburgh Tribune-Review reports is earmarked to improve street, pedestrian and bike transportation in the four-acre area surrounding the development.

Once one of the most thriving black business and cultural sectors in America, East Liberty was choked by transportation project decisions in the 1950’s. Over 1 million square feet of real estate was bulldozed for wider roads and shopping malls that led to displacement, pain and little else for many years.

Residents haven’t forgotten how poor planning has stunted their communities in the past, and Pittsburghers are thus extremely vocal about commercial real estate decisions in their city.

Last year, Whole Foods backed out of plans to build a 50,000 square-foot store in East Liberty after community uproar over the closure of an apartment complex on the lot.

On Pittsburgh’s North Side, a tenant council also blocked the eviction of more than 300 low-income families from Section 8 housing slated for redevelopment by acquiring a majority interest in the company that owns the property. The council, Northside Coalition for Fair Housing, contains to advocate to support resident control in the city.

Such activists have confronted the city of Pittsburgh at every turn of the Amazon deal, demanding to know details of the city’s bid as worries over who will be displaced by the possible headquarters grow.

After seeing how Amazon’s impact on Seattle and the rise of displacement and homelessness in the city, many Pittsburghers are wary of welcoming the tech giant. Amid chants of “Whose City? Our City!” at a recent gathering to discuss Pittsburgh’s bid of HQ2, activists and city leaders raised concerns about housing affordability. Mila Sanina, executive director of local investigative outlet PublicSource, said the project could have “as huge of an effect as the steel industry had on this city.”

Activists and city leaders are particularly concerned with Amazon considering the city’s Hazelwood Green area for the new headquarters. Three local organizations — The Heinz Endowments, the Richard King Mellon Foundation and the Claude Worthington Benedum Foundation — own most of the undeveloped property. The groups have released a major urban renewal plan that would see the 178-acre area surrounding a former LTV coke works slated for 4.3 million square feet of office and light industrial space and 3.8 million square feet of residential. The residential portion would be divided between three tiers of housing styles and alloted acres to account for the estimated 200 to 250 long-term, low-income households in the currently area.

“These 250 families really make us nervous,” said Rob Stephany, director of community and economic development at the Heinz Endowments, to the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette. “How do we keep them in place permanently, or at least for enough time that the development agenda can catch up with their needs? That’s the big thing that’s keeping everybody up at night.”

Hazelwood Green is already home to Uber, which built a test track — a fake city full of obstacles and roundabouts — for its autonomous cars on 42 acres in 2016. Carnegie Mellon University is also building housing two university robotics and manufacturing initiatives in Hazelwood Green’s Mill 19 building, which is part of the former Jones & Laughlin steel mill.

Like that steel mill and Google’s vanilla-scented office in the Nabisco plant, what is old is new for much of Pittsburgh’s latest commercial ventures. On another sweet note, an old Geoffrey Boehm Chocolates factory is now home to multiple robotics and self-driving startups in Lawrenceville.

“One of the things that is interesting about Pittsburgh is we have capacity in existing structures, and we don’t, compared to a lot of other markets, have a lot of new construction because we are able to reutilize a lot of buildings that are already downtown,” Jason Stewart, an executive vice president at JLL’s Pittsburgh office, told GeekWire.

With its industrial buildings and rail car inclines, Pittsburgh is a city where its history feels tangible and within reach. In a video pitch to Amazon, a narrator describes Pittsburgh as “the city that built America, the city that built the world, the city that fell so hard — and now, Pittsburgh the tech powerhouse.”

While clips of people tinkering with robots, getting down at banjo night and setting out a parking chair flash, the narrator makes the case for the city’s loyalty to a better tomorrow that Yinzers reach out to take for themselves. It’s a skill they’ve honed after facing the fires and hardships of yesterday, and the pitch heralds how we are forging new industries and sowing new seeds for a better tomorrow.

It invites you to come join the fun in Pittsburgh — before it’s too late. As the city’s most famous ambassador Mr. Rogers smiles welcomingly on screen, the growing city seeks to remind you there’s still always has room for “one more great neighbor.

Lead image via Wiki Commons